Executive Summary

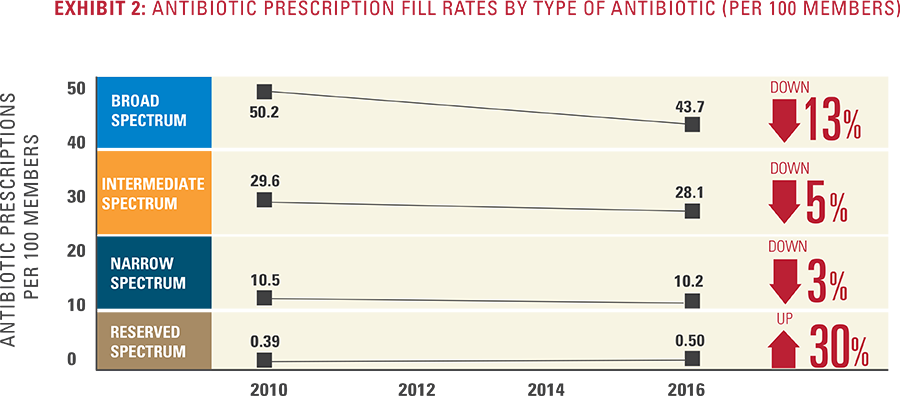

The overuse of antibiotics, which is known to cause antibiotic-resistant bacteria, has been a topic of concern among healthcare professionals and policy makers in America for many years.1 In particular, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics to treat a wide range of bacteria has been found to create antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria. These resistant bacteria are immune to common medications and are difficult to treat.2

The overuse of antibiotics, which is known to cause antibiotic-resistant bacteria, has been a topic of concern among healthcare professionals and policy makers in America for many years.1 In particular, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics to treat a wide range of bacteria has been found to create antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria. These resistant bacteria are immune to common medications and are difficult to treat.2

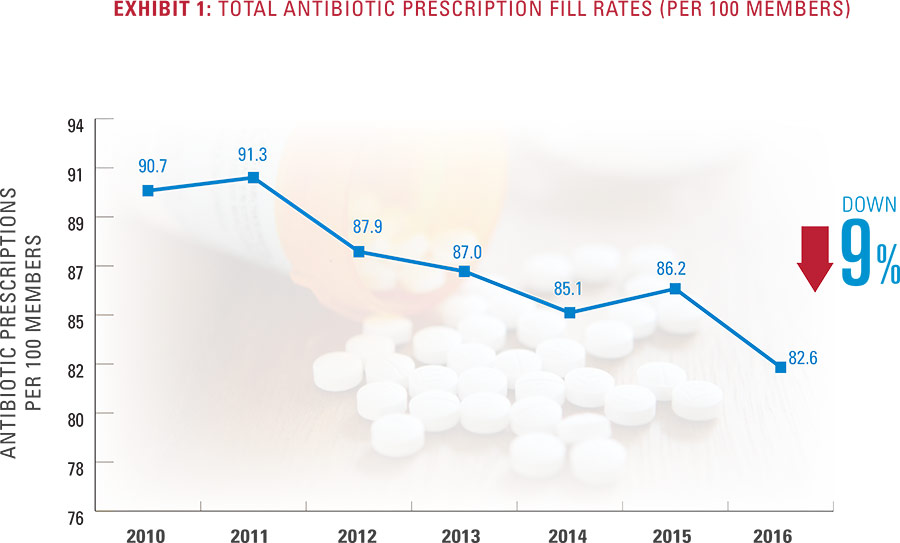

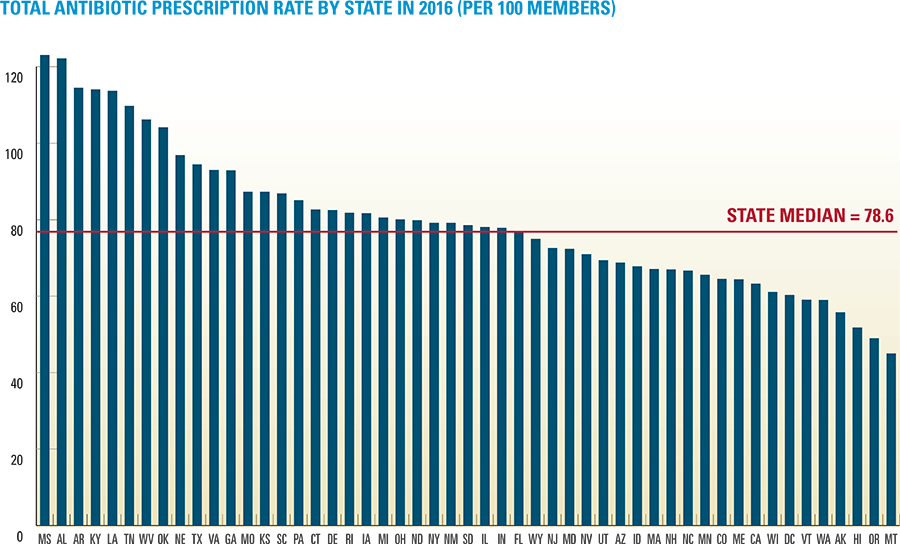

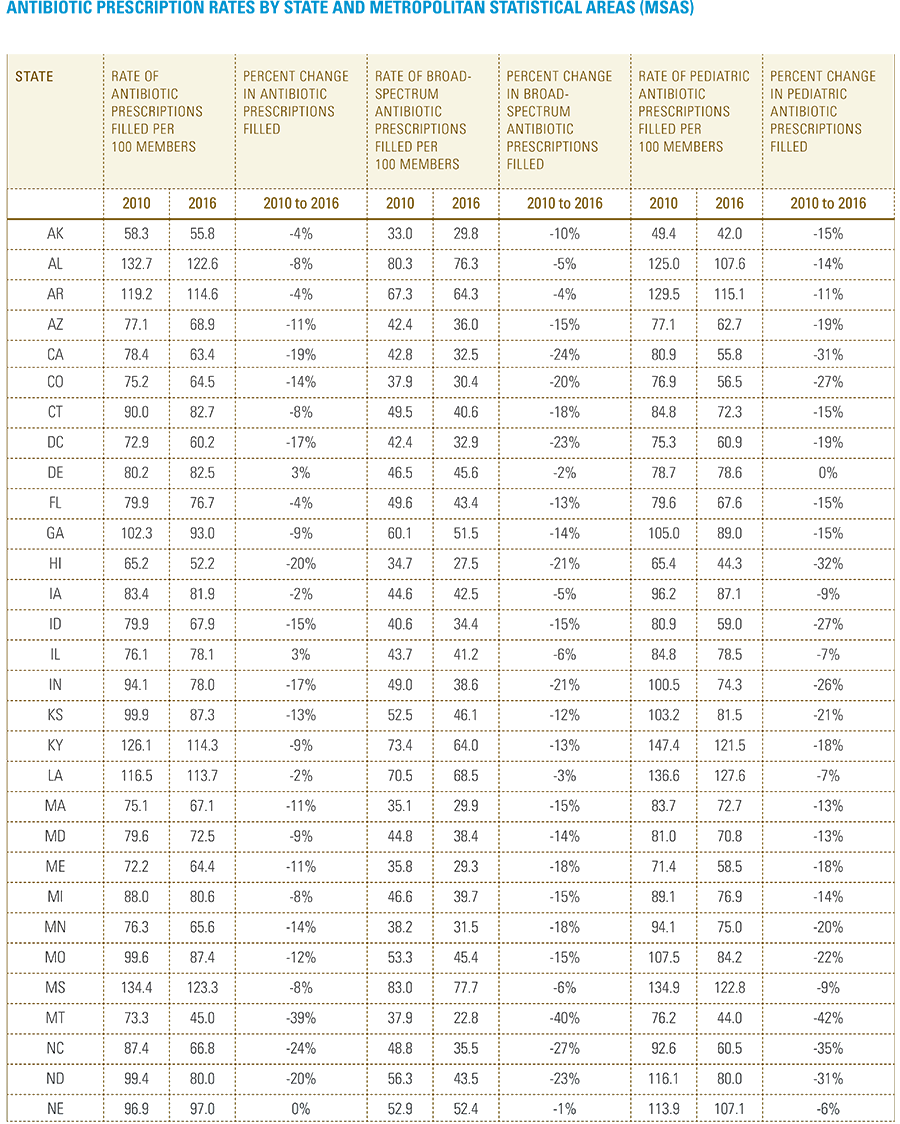

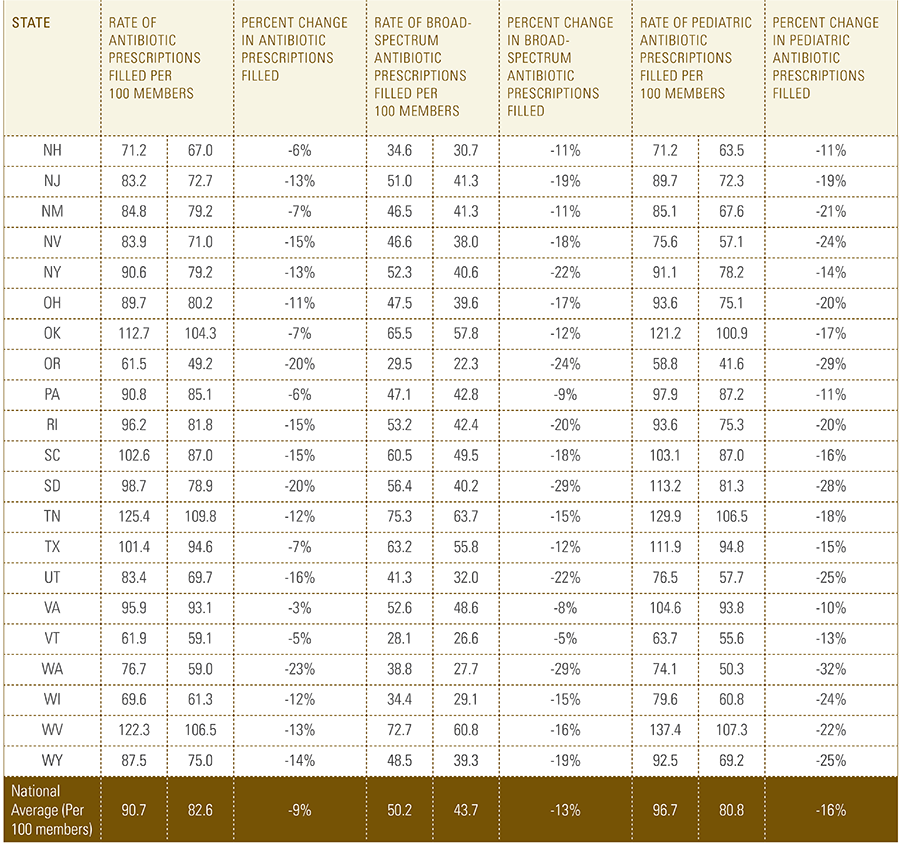

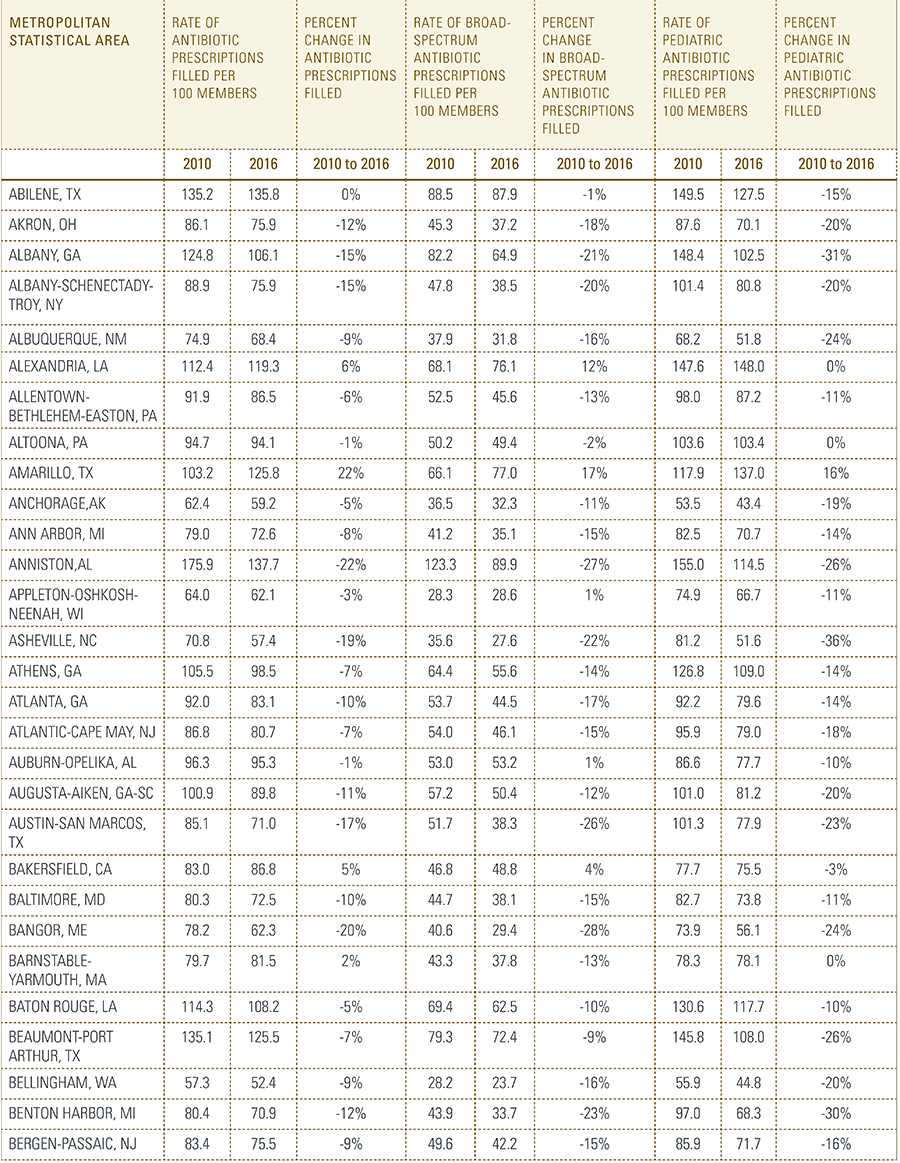

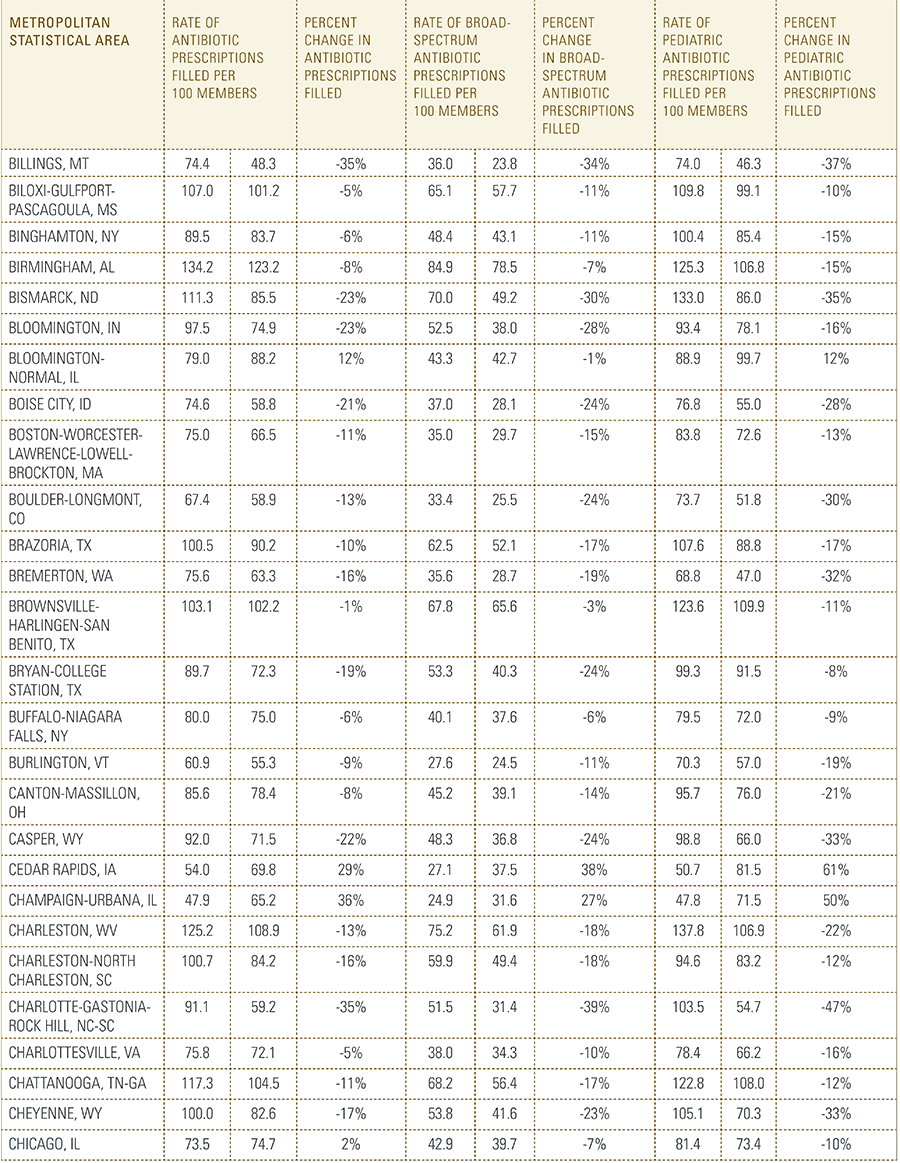

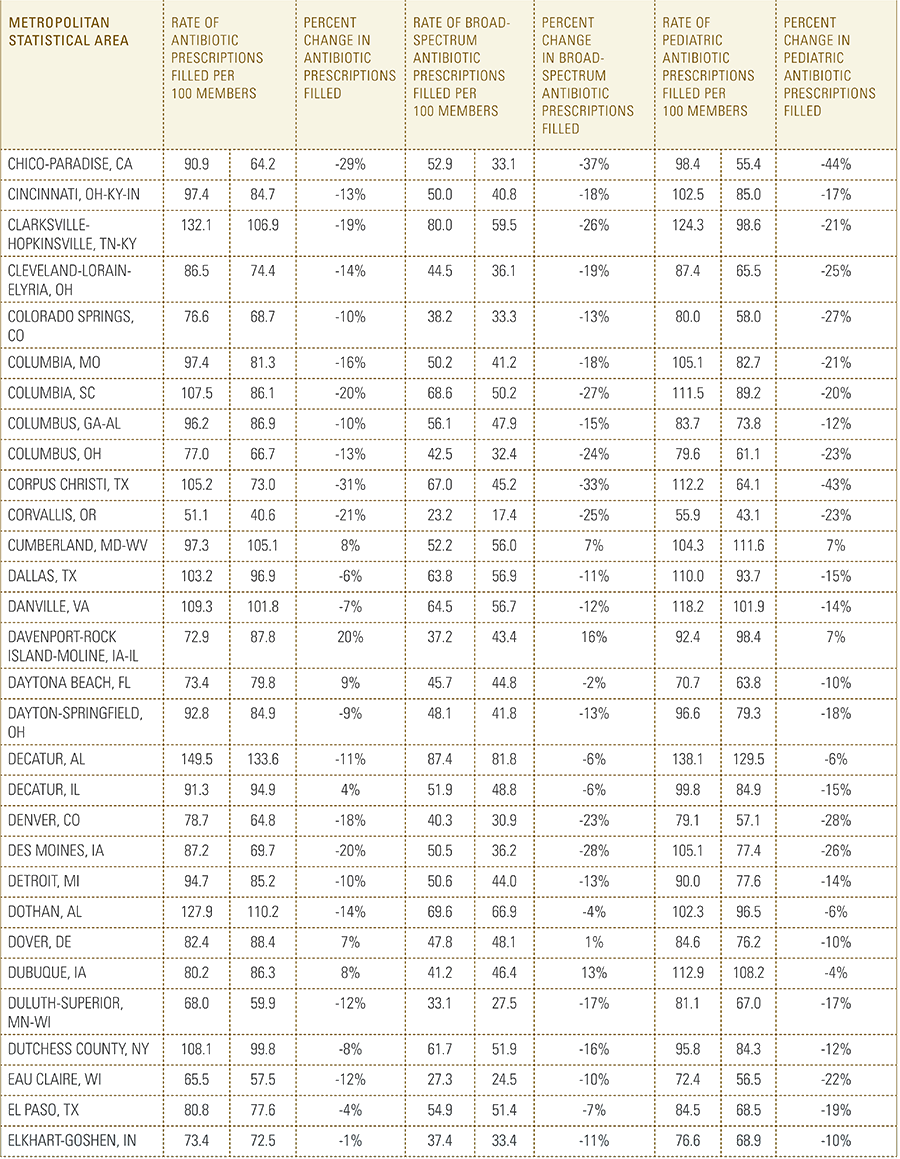

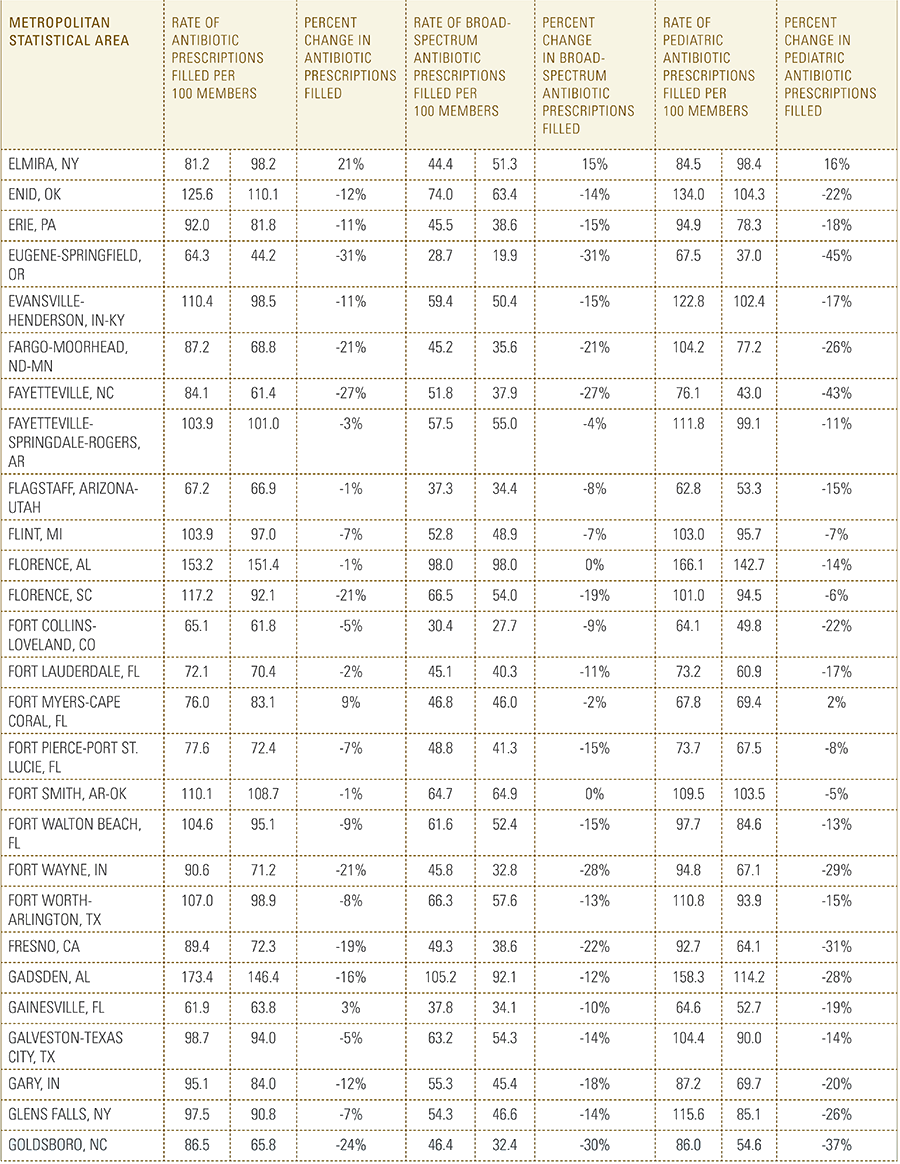

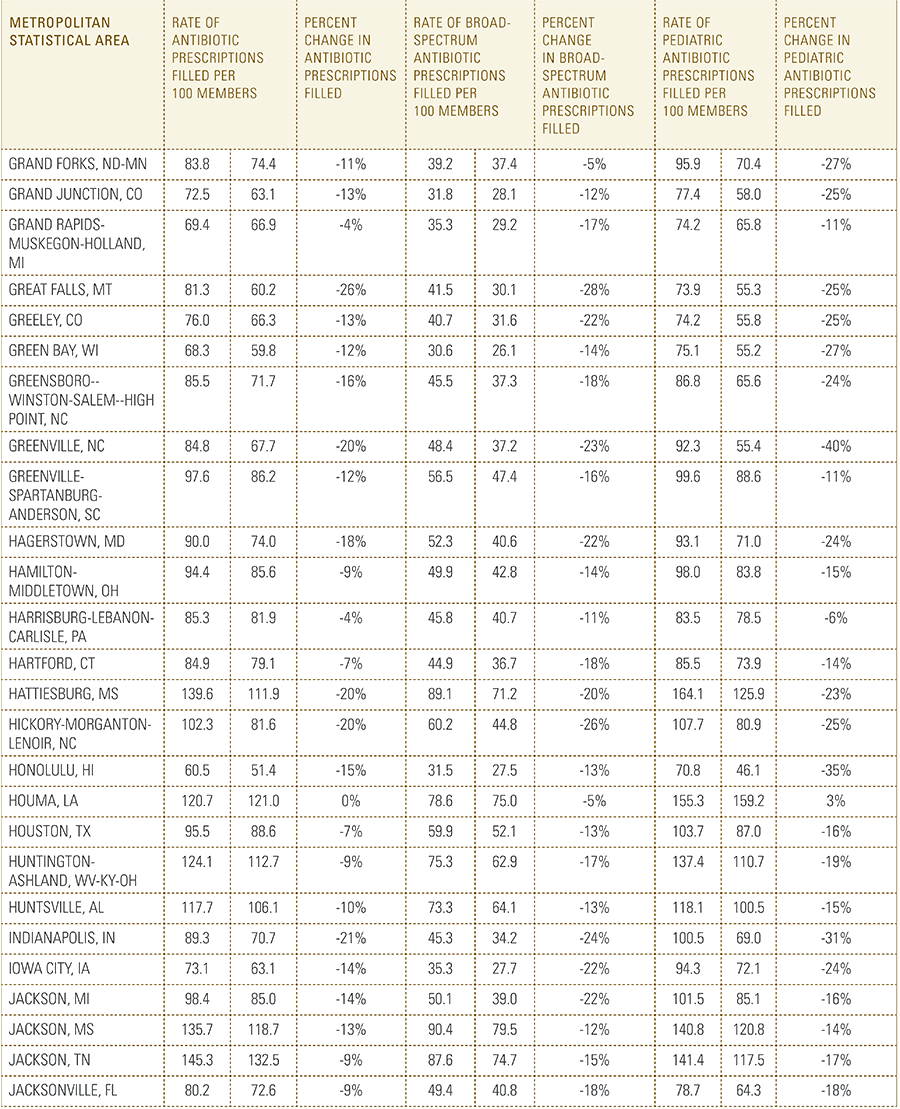

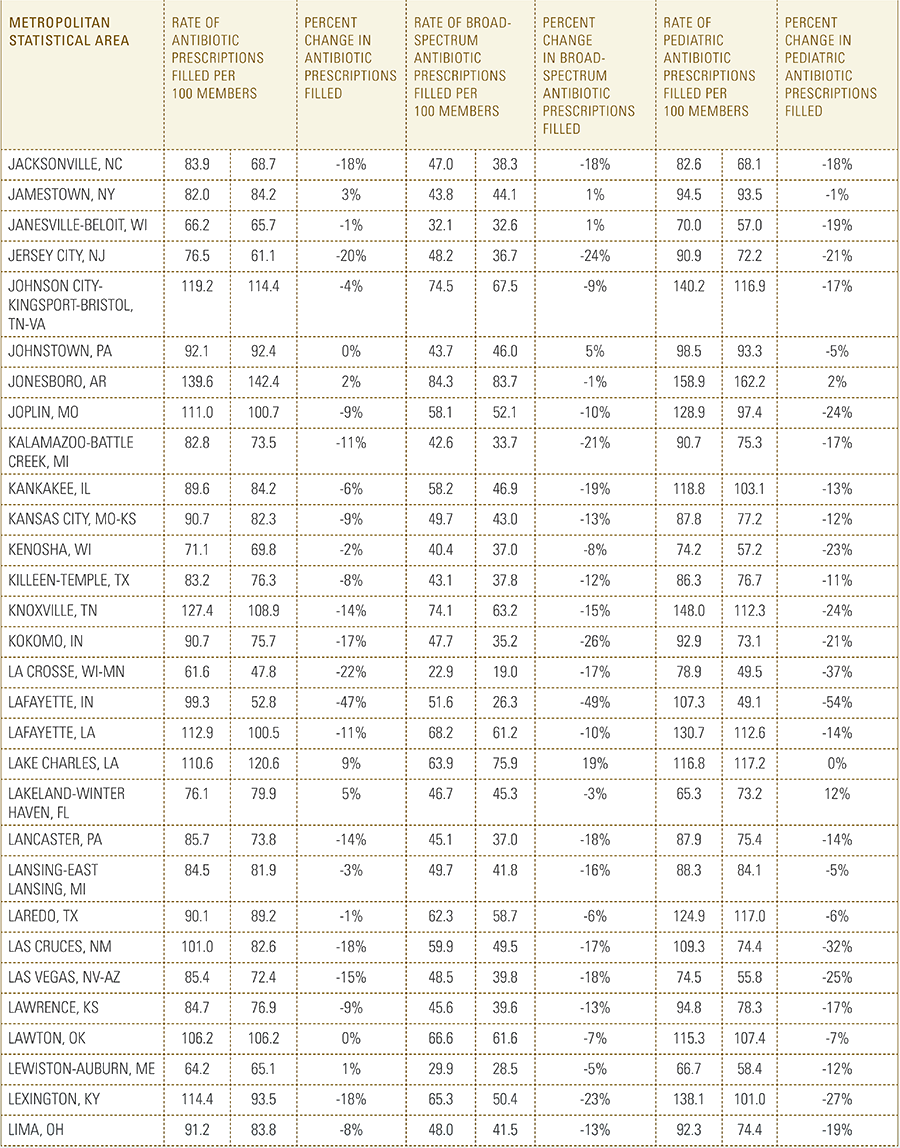

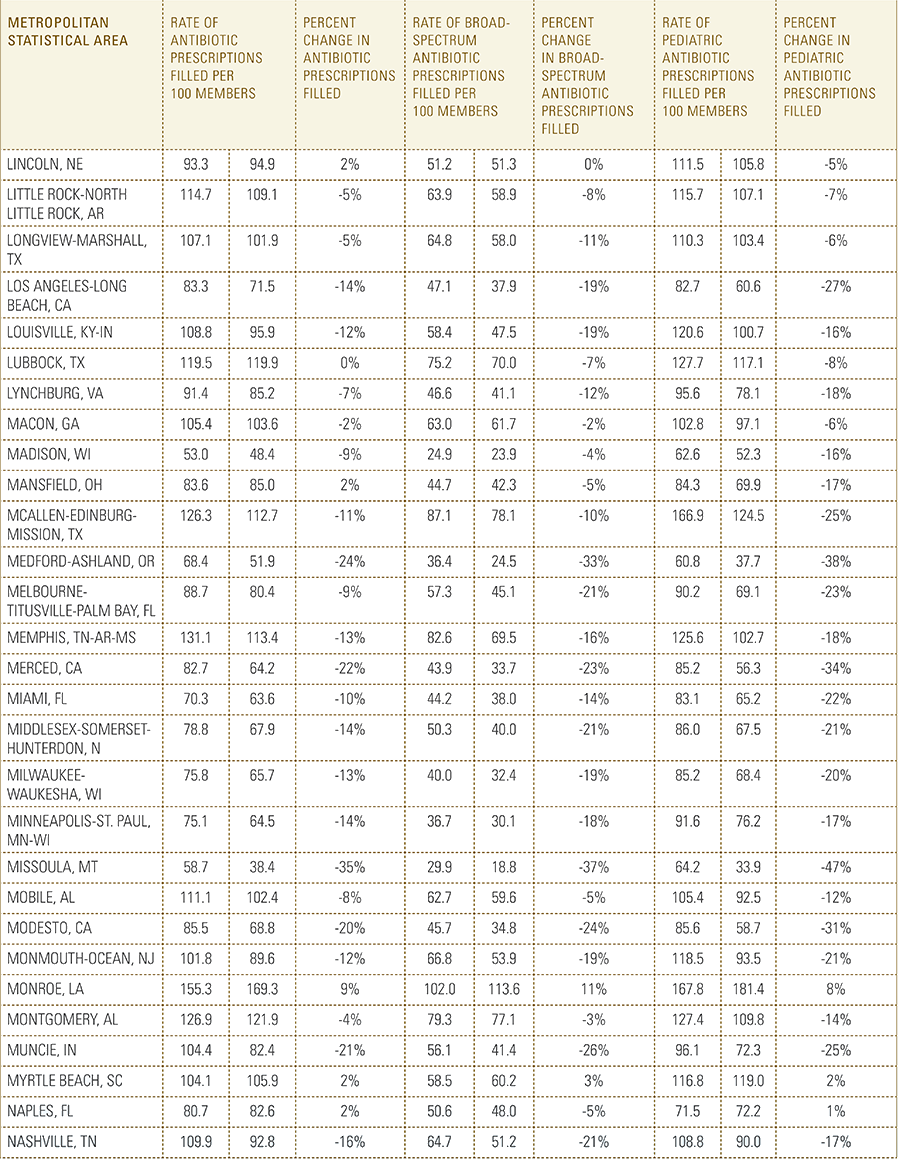

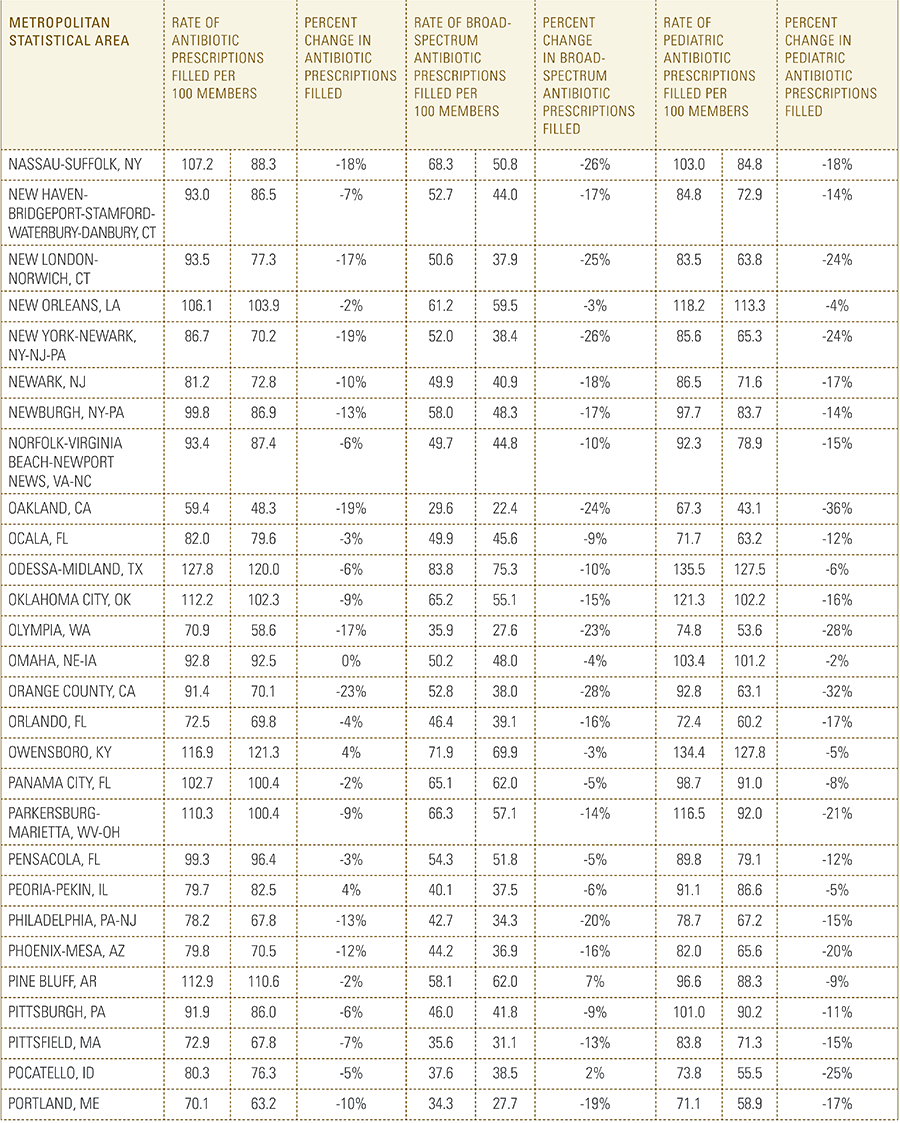

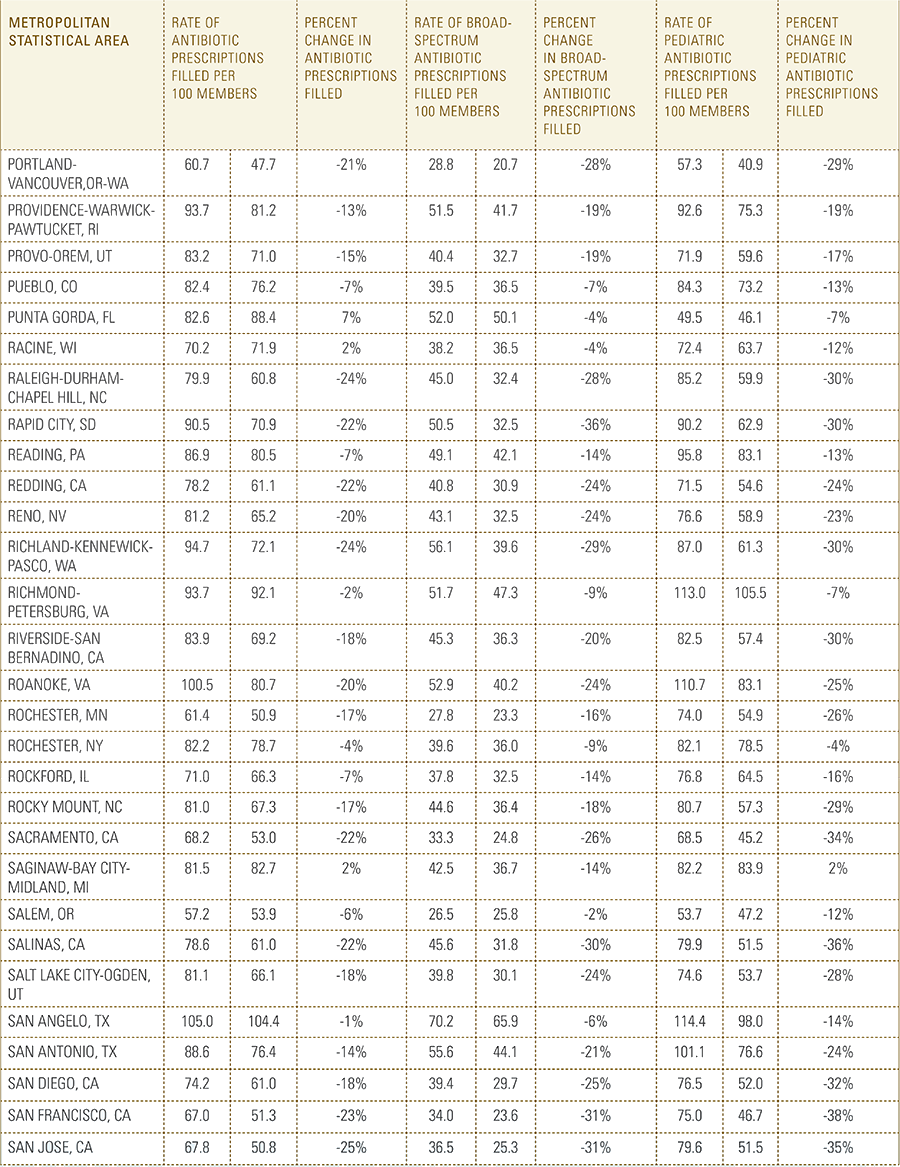

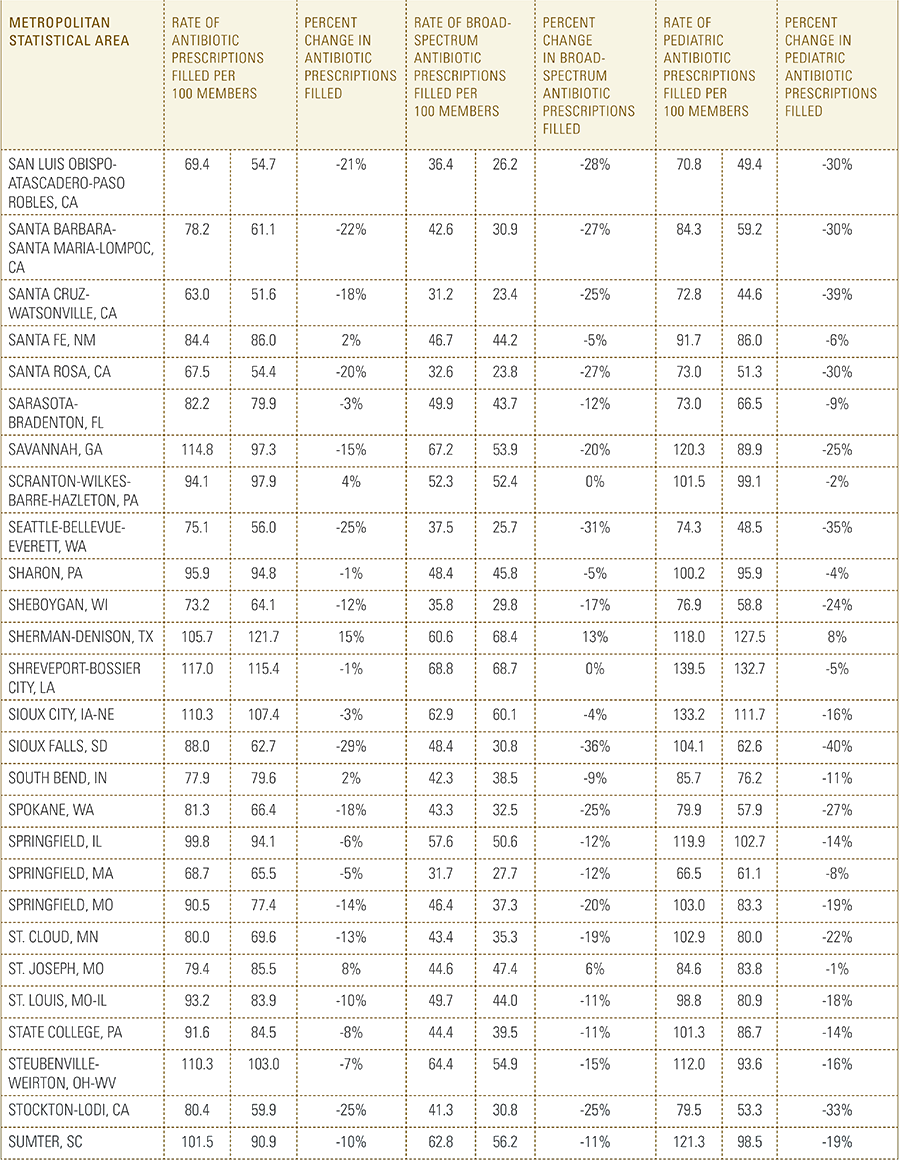

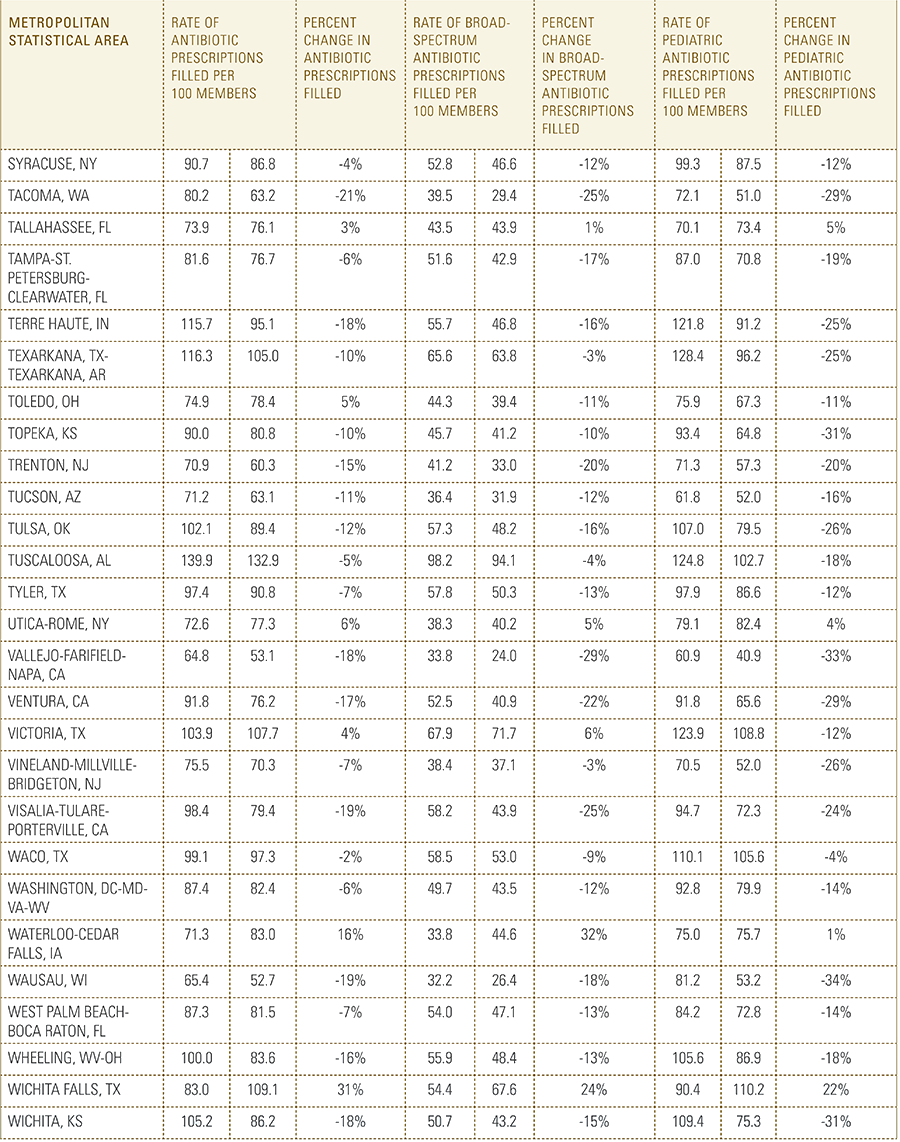

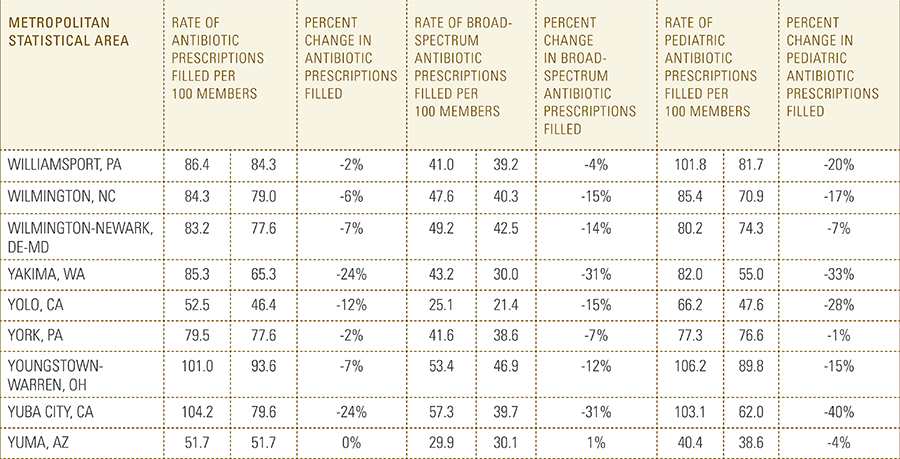

Since 2010, antibiotic prescription rates in the U.S. have been declining among the commercially insured population, falling 9 percent during this period. This decline indicates that considerable progress is being made in public health campaigns to limit the use of antibiotics and prevent the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

The Analysis

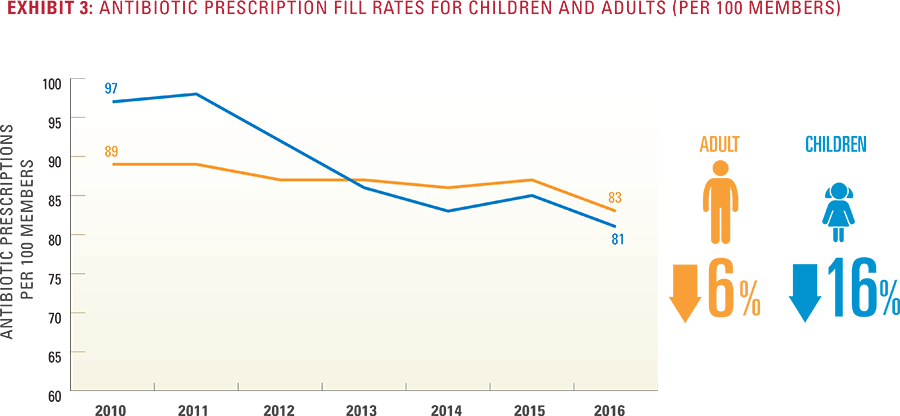

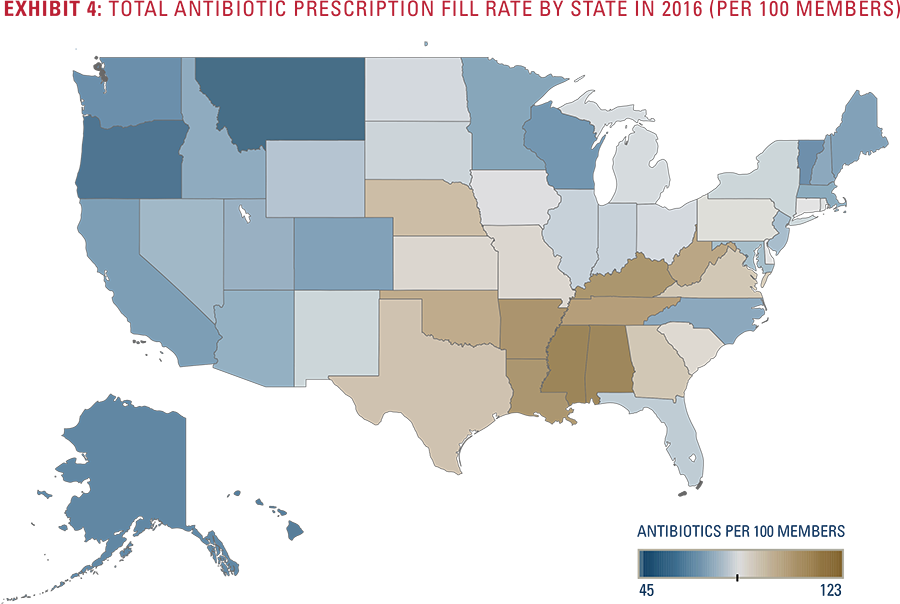

In this report, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, in partnership with HealthCore and Blue Health Intelligence, examine antibiotic prescriptions filled by commercially insured members from 2010 to 2016 as a result of an outpatient visit. Antibiotics administered as part of an inpatient visit were not included in this study. The scope of the research included 173 million patient claims for filled antibiotic prescriptions from over 31 million commercially insured Americans under age 65. This report includes antibiotics that were prescribed to and filled by a patient (referred to here as the antibiotic prescription fill rate), and are thereby considered as antibiotics used to treat a patient’s condition.

Summary of Key Findings

Summary of Key Findings Antibiotic Types

Antibiotic Types