The Achilles heel of population health? Measurement

Amidst the ongoing debate over healthcare in our nation, there is one subject on which there is nearly unanimous agreement: we must move the system toward delivering better health outcomes, while making efficient use of real resources. However, we have very little hard proof of which programs or practice have really improved health, or which evaluation methods can tell us what’s really working.

The real Achilles heel is that we cannot accurately measure health outcomes for the population, and so we cannot accurately measure quality – or reward it.

We find ourselves in this situation because getting a good measure of health that is both meaningful and “uncontaminated” is quite difficult. We need to compile a lot of data and interpret it in a careful way, and often the numbers we use — such as life expectancy at birth — are too crude and too biased to speak for themselves.

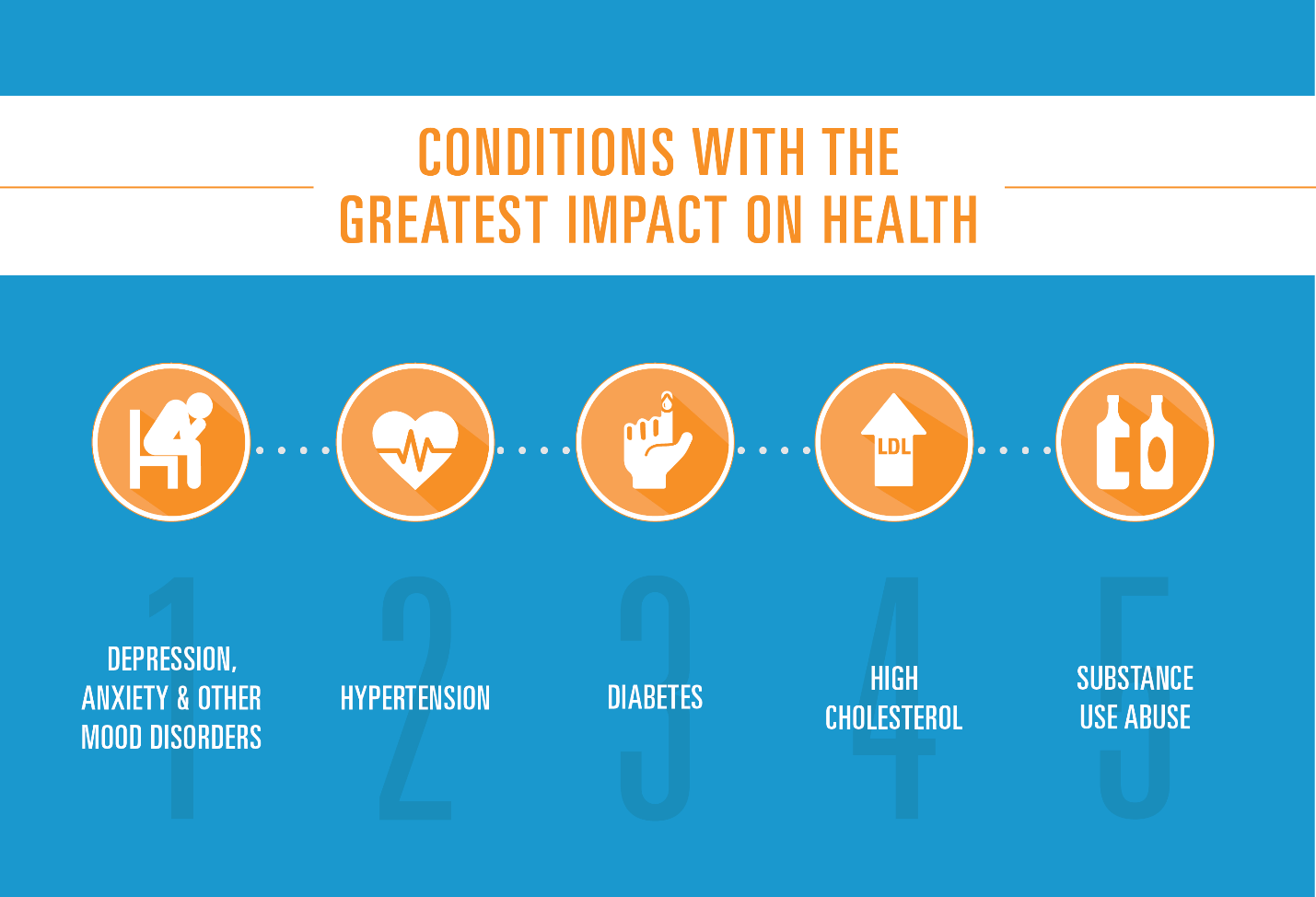

But now, the BCBS Health IndexSM provides an example of the kind of data effort that might be used to quantify and drive better outcomes. The BCBS Health IndexSM uses data from more than 40 million members insured by Blue Cross and Blue Shield (BCBS) companies, and explores the impact of 200 different diseases and conditions on the health and well-being of individuals and their communities from diabetes to depression.

Its most obvious use is being able to compare outcomes for insured individuals in different communities, and as such, may unearth previously undetected deficiencies and accomplishments.

But I am even more excited about it for another reason — it may be able to help Americans with the especially relevant question today of measuring whether and how taxpayer investments in expanding health insurance improve health. Current research on the impact of insurance on health often provides disappointing answers. For example, we see no gains on big picture measures like mortality and progress is limited to only a few conditions like depression. The exciting prospect is that the BCBS Health IndexSM can provide more sensitive measures of impacts and how they vary across communities.

Of course the initial form of the BCBS Health IndexSM is just a start. For example, it represents a limited but important subset of conditions, and it only applies to people buying BCBS plans. But the planned expansion of this effort and (from a self-interested viewpoint) the prospect that these measures might be made available to other researchers, all point to an optimistic future where data and facts can support policy.

We all know there is considerable progress to be made. The lesson here is, if we have enough good facts, like those unearthed from the BCBS Health Index,SM maybe we can get them to speak for themselves.